|

Natacha Soares Ribeiro

Investigadora

Researcher |

DA PERCEÇÃO DE APOIO ORGANIZACIONAL AO EMPENHAMENTO DOS VOLUNTÁRIOS

|

|

Em Portugal, é significativo o número de organizações da Economia Social que recorrem à força de trabalho voluntária (TV), seja como recurso principal, seja como complementar ou subsidiário ao pessoal assalariado. Segundo o INE – Instituto Nacional de Estatística, em 2918, o trabalho voluntário representou 45,9% do trabalho efetivo da ES, correspondendo a 214,5 milhões de horas a trabalho.

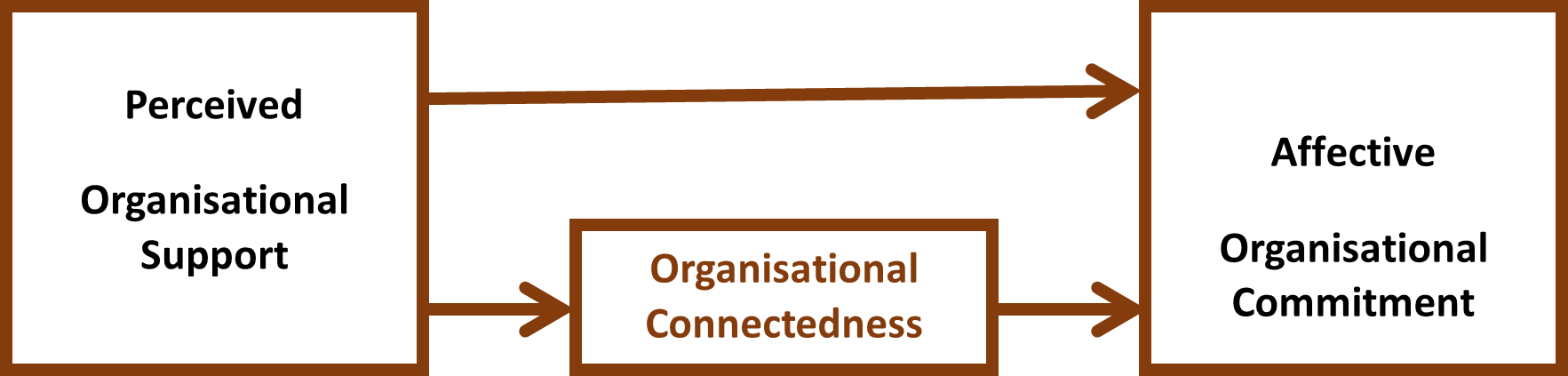

Embora o trabalho voluntário não seja compensado pecuniariamente, implica uma série de outros custos para a organização: o recrutamento de voluntários constitui uma tarefa dispendiosa e demorada (Hager & Brudney, 2004), e a integração de novos voluntários requer um significativo investimento de tempo e dinheiro uma vez que eles necessitam de se familiarizar com os processos e cultura organizacionais para que possam desempenhar bem as suas tarefas (Clary et al, 1992). A retenção de voluntários (principalmente dos mais competentes e empenhados) constitui, como tal, uma meta essencial para as muitas organizações que contam com a colaboração de voluntários para assegurar a prossecução da sua missão e servir eficaz e consistentemente os seus públicos-alvo. Entre outubro 2021 e abril de 2022, levei a cabo uma investigação académica [no âmbito do desenvolvimento da minha dissertação de Mestrado em Gestão de Recursos Humanos, pela Universidade do Minho] dedicada precisamente à temática da retenção de voluntários, com o objetivo de perceber como a perceção pelos voluntários do apoio que recebem da organização influencia o seu nível de empenhamento organizacional. Após revisão da literatura científica sobre a matéria, identifiquei outra variável com relevância para a compreensão dessa relação: a vinculação organizacional (ligação emocional ou sentimento de pertença). Pareceu-me importante aferir também até que ponto esta atua como mediadora na relação entre as outras duas variáveis, e contribui, como tal, para o aumento do empenhamento dos voluntários. A Problemática O relacionamento que se estabelece entre os voluntários e as organizações com que colaboram assume contornos estruturalmente distintos daquele que vincula os colaboradores remunerados. Em contexto do trabalho remunerado, a compensação pecuniária [aqui incluindo remuneração, prémios e outros benefícios] e o próprio contrato de trabalho atuam como instrumentos de promoção da retenção dos colaboradores, a ponto de haver pessoas que, mesmo insatisfeitas com aspetos relevantes da sua situação profissional (ex. as tarefas que desempenham, o ambiente de trabalho, o tratamento por parte seus superiores hierárquicos ou colegas, etc.), escolhem permanecer na organização. Ora, no contexto da gestão de voluntários, esses instrumentos não se aplicam, e a organização necessita de pensar em outros moldes o processo de captação e retenção de colaboradores. Devemos ter em conta que, na perspetiva da organização, embora o trabalho voluntário não implique uma compensação pecuniária, acarreta custos relevantes, que se traduzem na afetação de tempo e recursos [financeiros, humanos e técnicos] ao recrutamento, integração e suporte ao exercício da atividade voluntária, pelo que a saída de voluntários constitui um ónus relevante. O sucesso das organizações que recorrem ao trabalho voluntário depende não apenas da capacidade de motivar pessoas para se tornarem voluntários, mas também da capacidade de sustentarem os seus esforços de voluntariado ao longo do tempo (Alfes et al., 2015). Embora os motivos que influenciam inicialmente as pessoas a serem voluntárias possam diferir das que influenciam a sua decisão para permanecerem como voluntários (Gidron, 1984), é importante compreender a motivação inicial daqueles que permanecem como voluntários por um período mais longo. A ajuda sustentada dos voluntários indica que (a) os voluntários se sentem bem em relação ao significado do seu trabalho voluntário, (b) as organizações sem fins lucrativos são capazes de ter programas estáveis e poupar recursos no recrutamento, seleção, formação, e supervisão, e (c) os utentes beneficiam destes programas estáveis, implementados por voluntários motivados com quem eles poderão eventualmente desenvolver amizades, assim ganhando acesso e vínculos a redes naturais de apoio social (Omoto & Snyder, 2002). Hager & Brudney (2004) inventariaram um conjunto de nove práticas de gestão de voluntariado, que depois correlacionaram com outras características organizacionais e com a retenção dos voluntários. Essas práticas são: a supervisão e comunicação com os voluntários, a cobertura de responsabilidade para os voluntários, a triagem e adequação entre voluntários e funções, a recolha regular de informação sobre o envolvimento dos voluntários, políticas e descrição escrita de funções para os voluntários, atividades de reconhecimento, medição anual do impacto dos voluntários, formação e desenvolvimento profissional dos voluntários, e formação dos colaboradores remunerados sobre como trabalhar com os voluntários. Walk et al. (2019) também defendem que as práticas de recursos humanos desempenham um papel essencial na retenção dos voluntários, salientando a importância do reconhecimento dos voluntários através de prémios discricionários e da disponibilização de formação como práticas de recursos humanos que promovem, com especial eficácia, a retenção dos voluntários. Boezeman & Ellemers (2007) destacam a importância dos coordenadores de voluntários na indução de sentimentos de importância das atividades voluntárias para a organização, podendo por exemplo, fornecer aos voluntários feedback concreto sobre os seus esforços conjuntos na produção de um boletim de notícias físico ou online (por exemplo, comunicando o dinheiro angariado, descrevendo os projetos suportados, etc.), organizar reuniões informais entre os voluntários e os beneficiários da organização, para que os voluntários tenham a oportunidade de ouvir dos beneficiários o que os seus esforços significam para eles, prestar apoio orientado às emoções e apoio orientado à tarefa durante o trabalho voluntário, nomeadamente através do coordenador (que se assume como um elo entre a organização e o/a voluntário/a). Estes autores propõem que os coordenadores de voluntários sejam treinados para criar um ambiente nutridor no qual comunicam regularmente aos voluntários em funções o apreço da organização pelas suas doações de tempo e esforço e aferem como eles desejam ou necessitam ser apoiados na concretização do seu trabalho voluntário. Lo Presti (2013) também defende que, para assegurar que as experiências de voluntariado sejam altamente gratificantes e que os voluntários se comprometam mais é necessário que as organizações promovam condições caracterizadas por níveis mais elevados de apoio (direcionados quer à tarefa, quer à emoção), comunicação interna e feedback. A Intenção de Permanência na Organização – principais determinantes A Intenção de Permanência na Organização (IPO) por parte dos voluntários é identificada pelos teóricos e práticos de Gestão de Voluntários como um dos mais almejados resultados das práticas organizacionais, por possibilitar à organização reter os seus voluntários, gerir de forma mais eficiente os recursos financeiros e contar com um grupo de recursos humanos estável (condição indispensável para que se possa assegurar uma entrega consistente de serviços). Do vários constructos (conceitos) referenciados na literatura como influenciando direta ou indiretamente a intenção de permanência na organização, escolhi focar a atenção em três, procurando compreender como se relacionam, no contexto do voluntariado: a perceção de apoio organizacional, a vinculação organizacional e o empenhamento organizacional. A Perceção de Apoio Organizacional (Perceived Organizational Support) foi definida por Eisenberger et al. (1986) como o entendimento pelos colaboradores da medida em que a organização aprecia o seu contributo e se preocupa com o seu bem-estar. Levinston (1965, referido por Eisenberger et al., 1986) notou que os colaboradores tendem a ver as ações levadas a cabo por agentes da organização como ações da própria organização, sendo essa personalização da organização sustentada pelos seguintes fatores: a organização tem uma responsabilidade legal, moral e financeira pelas ações dos seus agentes; (b) precedentes organizacionais, tradições, políticas e normas proporcionam continuidade e prescrevem comportamentos de função; e (c) a organização, através dos seus agentes, exerce poder sobre os colaboradores individuais. Os colaboradores desenvolvem crenças globais relativas ao quanto a organização valoriza as suas contribuições e se preocupa com o seu bem-estar, dependendo esta perceção de apoio organizacional dos mesmos processos atributivos que as pessoas geralmente usam para inferir o empenhamento de outras pessoas às relações sociais - em última análise, o empenhamento dos colaboradores para com a organização é fortemente influenciado pela sua perceção do empenhamento da organização para com eles. A Vinculação Organizacional (Organisational Connectedness) é definida como um estado positivo de bem-estar que resulta de uma forte sensação individual de pertença relativa aos restantes colaboradores da organização ou aos beneficiários do serviço (Huyn et al., 2011). Pode manifestar-se na procura por um ser humano de vínculo interpessoal, assim como na necessidade de vínculo ao próprio trabalho ou aos valores da organização. O Empenhamento Organizacional (Organisational Commitment) é definido como um estado psicológico que caracteriza a relação entre o trabalhador e a organização e traduz-se na disposição do indivíduo dedicar um significativo tempo e esforço à organização sem ser com um objetivo monetário (Meyer e Allen, 1997). Este é um dos constructos do comportamento organizacional mais estudados em contexto de gestão de voluntários e das próprias organizações sem fins lucrativos, pois é associada por teóricos e práticos da gestão a resultados especialmente valorizados em contexto organizacional: lealdade, não abandono da atividade (Mowen et al., 1978), uma prestação de serviço de maior qualidade e a intenção de envolvimento de longa-duração com a organização (Salas, 2009, citado por Séfora, 2016). O empenhamento organizacional é considerado como um dos principais preditores da intenção de permanência dos voluntários na organização (Salas, 2009; Vecina et al. 2013). O empenhamento constitui um constructo multidimensional, distinguindo-se normalmente as dimensões afetiva, a instrumental e a normativa. No âmbito da nossa investigação, isolámos o empenhamento afetivo, que se refere especificamente ao vínculo emocional ou psicológico, à identificação com e participação na organização (Meyer & Smith, 2000). O empenhamento afetivo traduz uma relação forte entre um determinado indivíduo e uma organização específica, e pode ser caracterizado por 3 fatores: (1) estar disposto a exercer esforço considerável em benefício da organização; (2) uma forte crença e aceitação dos objetivos e valores da organização; e (3) um forte desejo de se manter como membro da organização (Porter & Smith,1979). O Modelo Conceptual Figura 1

Modelo conceptual O modelo conceptual, construído a partir da revisão de literatura, que serviu de base à nossa investigação, propõe (1) que existe uma relação causal direta entre a perceção de apoio organizacional e o empenhamento organizacional afetivo, e (b) que a vinculação organizacional poderá desempenhar um papel mediador na relação entre perceção de apoio organizacional e empenhamento organizacional afetivo. Recolha e análise dos dados A partir do modelo, construí um questionário que teve como destinatários pessoas que exercem ou exerceram voluntariado regular, tendo uma colaboração mínima, com a mesma organização, de um ano. O critério de um ano de colaboração com a mesma organização teve como finalidade garantir um tempo mínimo de exposição à vivência na organização e às práticas da mesma. Para além de perguntas de caracterização da amostra, o questionário integrou três escalas já testadas no âmbito da literatura científica: a escala utilizada no Inquérito à Perceção de Apoio Organizacional (Eisenberger et al, 1986); a Escala Tetradimensional de Vinculação (Huyn et al., 2012); e a Escala Tridimensional de Empenhamento Organizacional (Dawley et al., 2005)], tendo os itens da primeira e segunda escalas sido adaptadas ao contexto voluntário (este procedimento não foi necessário para a terceira escala, onde essa adaptação já tinha sido feita pelos próprios autores). Ciente da importância de submeter o questionário ao maior número possível de voluntários, contactei a CASES – Cooperativa António Sérgio para a Economia Social, com o pedido de que o encaminhasse à sua base de dados de voluntários. A resposta da Cases, operacionalizada pela Dra. Paula Correia e pela Dra. Teresa Lucas, superou as minhas expectativas, e pude contar não apenas com a anuência ao meu pedido, mas também com uma competente e empenhada colaboração na afinação do questionário. Solicitei também a um universo de 700 organizações sem fins lucrativos o encaminhamento do questionário aos seus voluntários, tendo este pedido acolhido favoravelmente por várias organizações. 323 voluntários decidiram amavelmente responder ao questionário, tendo sido reportada por este conjunto de pessoas uma colaboração regular (presente ou passada) com um total de 218 organizações com fins não lucrativos portuguesas, assim como experiência de voluntariado num total de 50 países, incluindo Portugal. Os dados recolhidos foram analisados com recurso à estatística descritiva e à análise de equações estruturais (através do programa SmartPLS 3). Resultados Como referi, esta pesquisa foi desenhada com a finalidade de se compreender a relação entre a perceção de apoio organizacional e o empenhamento organizacional afetivo, considerado preditor da decisão de permanência na organização, e de avaliar o possível papel de mediação desempenhado pela vinculação organizacional nessa relação. A pesquisa produziu resultados positivos em matéria de estabelecer a fiabilidade e validade dos instrumentos de medida propostos. A análise quantitativa dos dados confirmou a existência de uma relação causal entre a perceção de apoio organizacional e o empenhamento organizacional afetivo, assim como a hipótese de que a vinculação organizacional atua efetivamente como mediadora total nessa relação. Numa linguagem corrente, significa isto que quanto mais os voluntários percebem que são cuidados pela organização (quer no âmbito das funções e tarefas que desempenham, quer em termos emocionais, quando oportuno ou necessário) mais tendem a dedicar-se à organização, e a assumir comportamentos favoráveis à prossecução da missão e dos objetivos organizacionais. Como disseram Eisenberger et al. (1986), o empenhamento dos colaboradores para com a organização é fortemente influenciado pela sua perceção do empenhamento da organização para com eles. Para além disso, verifica-se que o impacto da perceção de apoio organizacional é alavancada significativamente, com impacto no empenhamento organizacional afetivo, quando os voluntários sentem um forte sentimento de pertença (vinculação) em relação à organização. Implicações Teóricas e Práticas da Investigação Em contexto de voluntariado, no qual a organização não dispõe das clássicas ferramentas de controlo - remuneração e contrato de trabalho - é essencial que o/a voluntário/a sinta que tem razões para permanecer na organização. Os itens de perceção de apoio organizacional (Eisenberger et al., 1986) e de vinculação organizacional (Huyn et al., 2012) do questionário selecionados para os modelos após a análise das equações estruturais (por terem maior carga fatorial) dão aos gestores de voluntários boas pistas para que possam compreender o que verdadeiramente pode criar a vinculação de um voluntário à organização e nutrir o seu empenhamento em relação à mesma: “A organização valoriza a minha contribuição para o seu bem-estar (PAO); a organização tem seriamente em conta as minhas metas e os meus valores (PAO); quando tenho um problema, conto com ajuda da organização (PAO); a organização está disponível para me ajudar quando eu necessito de um favor especial (PAO); a organização preocupa-se com a minha satisfação geral no trabalho voluntário (PAO); a organização é sensível às minhas opiniões (PAO); a organização orgulha-se dos meus sucessos (PAO); a organização procura tornar o meu trabalho o mais interessante possível (PAO); Dou-me bem com os meus pares e com os funcionários da organização (VO); sou apreciado pelas pessoas com que trabalho (VO); tenho um sentimento de pertença em relação às pessoas com que trabalho na organização (VO); sinto gosto em fazer trabalho voluntário (VO); sou valorizado pela organização (VO); os meus esforços, enquanto voluntário/a são valorizados pela organização (VO); a organização aprecia o meu esforço (VO); sou tratado/a de forma justa pela organização (VO)”. É importante que as organizações que escolhem contar com voluntários como força de trabalho, principal ou complementar, sejam plenamente conscientes:

Na sua maioria, os voluntários escolhem de livre vontade colaborar com a organização, movidos por fatores como a identificação com a missão da organização; o conhecimento prévio da atividade da organização; o ter sido inspirado/a pelos/as líderes da organização. Subjacentes a estes motivos, existem as necessidades que os voluntários querem satisfazer, muitas vezes de forma inconsciente. A atividade de voluntariado é, frequentemente, o contexto em que a pessoa consegue satisfazer necessidades emocionais básicas como são o afeto, a valorização e a segurança, ou mesmo necessidades não tão básicas como o desenvolvimento de competências com aplicabilidade profissional, a criação de uma rede de contactos, a busca do sentido da vida, ou mesmo a realização pessoal. Mas, para que a satisfação dessas necessidades aconteça de forma consistente, dando aos voluntários razões para quererem permanecer, a organização deve criar um ambiente e condições adequadas, e isso só acontece quando: (1) existe uma atitude de respeito e acolhimento relativamente aos voluntários, que são cuidadosamente integrados e autenticamente considerados como membros de pleno direito da organização; (2) existe um olhar atento a cada voluntário/a para que as suas necessidades e motivações sejam compreendidas e as suas competências, preferências e condicionantes sejam tidas em consideração na escolha das tarefas, dos desafios, das equipas de trabalho, dos horários e até do tipo de utentes que irão servir; (3) existe na organização quem se dedique prioritariamente aos voluntários, na qualidade de clientes internos, sem a satisfação e envolvimento dos quais poderá tornar-se impraticável a prestação ao cliente externo, o beneficiário da organização; (4) existe um esforço consciente e consistente de planeamento e gestão de voluntários que tenha em consideração as especificidades e contingências da organização concreta e consiga desenvolver e implementar atitudes e práticas organizacionais que assegurem o apoio eficaz (ao trabalho e às emoções) dos colaboradores voluntários, que seja percebido como tal, que nutra a ligação emocional (vinculação) dos colaboradores à organização e que, em última análise, promova o comprometimento organizacional - não se trata de implementar todas a práticas de gestão de voluntários, antes de perceber quais é que produzem melhores resultados, no contexto daquela organização em particular e, se possível, com menos esforço e afetação de recursos (particularmente nas organizações com maior fragilidade em matéria de recursos); (5) existe a consciência de que a forma como se implementa cada prática influencia mais a perceção por parte dos voluntários do que a própria prática - e nessa medida, não podemos deixar de salientar a importância da comunicação, que sendo uma da práticas de gestão de voluntários anteriormente identificadas, é possivelmente aquela que, se adequadamente implementada, pode responder de forma mais direta às necessidades emocionais básicas dos voluntários, e garantir a adequação e eficácia de todas as outras que se entender por bem implementar (formação, reconhecimento). Por vezes, uma palavra de apreço no fim de um turno difícil de voluntariado, por parte de um colega ou de um coordenador, ou uma conversa de motivação perante uma dificuldade, são mais significativos para a pessoa que exerce voluntariado do que aquele prémio de reconhecimento que recebe, num palco, perante centenas de pessoas, no final no ano. Tornam-se preciosos aqueles momentos em que, numa ação de formação ou numa atividade de equipa, se inicia uma nova amizade; ou quando se tem a oportunidade de conhecer pessoalmente alguns beneficiários do trabalho voluntário, com quem ainda só se falara por telefone; ou em que se pode ajudar a fazer acontecer através da expressão de algum dos talentos pessoais (marcenaria, cozinha, pintura, reparação, escrita, desenho, dança, ou outros). Se pudéssemos sintetizar em algumas palavras o que pretende uma parte significativa dos voluntários será sentirem que são queridos e valorizados, que importam, que são úteis, que estão a aprender e a desenvolver-se, que são capazes de fazer a diferença na vida de alguém. Os coordenadores de voluntários desempenham um papel fulcral neste âmbito, sendo importante que possam assumir os voluntários como seus principais clientes internos - e não como mais um recurso a usar para servir os beneficiários e concretizar as metas organizacionais. Na linha do que defendem Lo Presti (2013) e Boezeman & Ellemers (2007), referidos anteriormente, consideramos que, ao cuidar-se, contínua e consistentemente (desde o primeiro contacto), a relação entre o voluntário e todo o universo humano da organização (outros voluntários, equipa de gestão, colaboradores remunerados, utentes) é possível criar-se experiências verdadeiramente gratificantes e significativas, que promovam o sentimento de pertença e de importância, passíveis de desenvolver voluntários felizes e verdadeiramente empenhados para com a organização. BIBLIOGRAFIA

ALFES, K, SHANTZ, A. & BAILEY, C. (2015). Enhancing volunteer engagement to achieve desirable outcomes: What can non-profit employers do? VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 27, 595-617. BOEZEMAN, E. J., & ELLEMERS, N. (2007). Volunteering for charity: Pride, respect, and the commitment of volunteers. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92, 771-785. CLARY, E. G., SNYDER, M., & RIDGE, R. (1992). Volunteers' motivations: A functional strategy for the recruitment, placement, and retention of volunteers. Nonprofit Management and leadership, 2 (4), 333-350. DAWLEY, D, STEPHENS, R. & STEPHENS, D. (2004). Dimensionality of organizational commitment in volunteer workers: Chamber of commerce board members and role fulfillment. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 67 (2): 511-525. EISENBERGER, R., HUNTINGTON, R., HUTCHISON, S. & SOWA, D. (1986). Perceived Organizational Support. Journal of Applied Psychology, 71 (3), 500-507. The American Psychological Association. GIDRON, B. (1984). Predictors of retention and turnover among service volunteer workers. Journal of social service research, 8 (1), 1-16. HAGER, M. A., & BRUDNEY, J. L. (2004). Balancing act: the challenges and benefits of volunteers. Washington: The Urban Institute. HAGER, M. A., & BRUDNEY, J. L. (2011). Problems Recruiting Volunteers - Nature vs Nurture. Nonprofit Management & Leadership, 22, n.2. HUYNH, J. Y., METZER, J. C., & WINEFIELD, A. H. (2011). Engaged or connected? A perspective of the motivational pathway of the job demands-resources model in volunteers working for nonprofit organizations. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 23 (4), 870-898. LO PRESTI, A. (2013). The interactive effects of job resources and motivations to volunteer among a sample of Italian Volunteers. Voluntas – International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 24 (2), 969-985. MEYER, J.P.& ALLEN, N.J. (1997). Commitment in the workplace: Theory, Research and Application. SAGE Publications MEYER, J. P., & SMITH, C. A. (2000). HRM practices and organizational commitment: Test of a mediation model. Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences/Revue canadienne des sciences de l'administration, 17 (4), 319-331. MOWDAY, R. T., STEERS, R. M., & PORTER, L. W. (1979). The Measurement of Organizational Commitment. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 14, 224-247. Omoto, A. & Snyder, M. (1995), Sustained helping without obligation: motivation, longevity of service and perceived attitude change among aid volunteers. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 68 (4), 671-86. SALAS, Emílio (2009). Claves para la Gestión del Voluntariado en las Entidades no Lucrativas. Madrid: Fundación Luis Vives. SEFORA, N. S. M., & MIHAELA, T. T. (2016). Volunteers trust in organizational mission, leadership and activities efficiency. annals of the university of Oradea, Economic Science Series, 25 (1). VECINA, M. L., CHACÓN., F., MARZANA, D. & MARTA, E. (2013). Volunteers Engagement and Organizational Commitment in Nonprofit Organizations: what makes volunteers remain within organizations and feel happy? Journal of Community Psychology, 41, (3), 291-302. WALK, M., ZHANG, R., & LITTLEPAGE, L. (2019). “Don't you want to stay?” The impact of training and recognition as human resource practices on volunteer turnover. Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 29 (4), 509-527. |

In Portugal, the number of Social Economy organisations that make use of the volunteer work (VW) is significant, either as a main resource or as a complementary or subsidiary resource to salaried staff. According to INE - National Institute of Statistics, in 2018, volunteer work represented 45.9% of the effective work of HE, corresponding to 214.5 million hours of work.

Although volunteer work is not compensated monetarily, it entails a number of other costs for the organisation: recruiting volunteers is a costly and time-consuming task (Hager & Brudney, 2004), and integrating new volunteers requires a significant investment of time and money as he/she needs to become familiar with organisational processes and culture in order to perform their tasks well (Clary et al, 1992). Therefore, retaining volunteers (especially the most competent and committed ones) is a key goal for the many organisations that rely on the collaboration of volunteers to ensure the pursuit of their mission and to serve their target audiences effectively and consistently. Between October 2021 and April 2022, I conducted an academic research [as part of the development of my Master's dissertation in Human Resource Management at the University of Minho] dedicated precisely to the issue of volunteer retention, with the objective of understanding how volunteers' perception of the support he/she receives from the organisation influences their level of organisational commitment. After reviewing the scientific literature on the subject, I identified another relevant variable for understanding this relationship: organisational connectedness (emotional connection or sense of belonging). It also seemed important to assess to what extent it acts as a mediator in the relationship between the other two variables and, as such, contributes to increasing volunteers' commitment. The Problem The relationship established between volunteers and the organisations with which he/she collaborates is structurally different to that between paid employees. In the context of paid work, monetary compensation (including remuneration, bonuses and other benefits) and the employment contract itself act as instruments to promote employee retention, to the extent that there are people who, even if dissatisfied with relevant aspects of their professional situation (e.g. the tasks he/she performs, the working environment, the treatment by their superiors or colleagues, etc.), choose to remain in the organisation. However, in the context of volunteer management, these instruments do not apply, and the organisation needs to think in other ways about the process of attracting and retaining employees. We must take into account that, from the perspective of the organisation, although volunteer work does not imply monetary compensation, it entails relevant costs, which translate into the allocation of time and resources [financial, human and technical] to recruit, integrate and support the exercise of the volunteer activity, so that the departure of volunteers constitutes a relevant burden. The success of organisations that make use of volunteer work depends not only on their ability to motivate people to become volunteers, but also on their ability to sustain their volunteering efforts over time (Alfes et al., 2015). While the motives that initially influence people to volunteer may differ from those that influence their decision to remain as volunteers (Gidron, 1984), it is important to understand the initial motivation of those who remain as volunteers for a longer period. Sustained volunteer help indicates that (a) volunteers feel good about the meaning of their volunteer work, (b) non-profit organisations are able to have stable programmes and save resources on recruitment, selection, training, and supervision, and (c) users benefit from these stable programmes implemented by motivated volunteers with whom they may eventually develop friendships, thus gaining access and links to natural social support networks (Omoto & Snyder, 2002). Hager & Brudney (2004) inventoried a set of nine volunteer management practices, which they then correlated with other organisational characteristics and volunteer retention. These practices are: supervision and communication with volunteers, responsibility coverage for volunteers, screening and matching volunteers to roles, regular collection of information on volunteer involvement, written policies and job descriptions for volunteers, recognition activities, annual measurement of volunteer impact, training and professional development for volunteers, and training for paid employees on how to work with volunteers. Walk et al. (2019) also argue that human resource practices play a key role in volunteer retention, highlighting the importance of recognising volunteers through discretionary awards and the provision of training as human resource practices that particularly effectively promote volunteer retention. Boezeman & Ellemers (2007) highlight the importance of volunteer coordinators in inducing feelings of importance of volunteer activities for the organisation, they can for example provide volunteers with concrete feedback on their joint efforts in producing a physical or online newsletter (e.g. communicating money raised, describing supported projects, etc.), organise informal meetings between volunteers and the organisation's beneficiaries so that volunteers have the opportunity to hear from the beneficiaries what their efforts mean to them, provide emotion-oriented support and task-oriented support during volunteer work, notably through the coordinator (who is assumed to be a link between the organisation and the volunteer). These authors propose that volunteer coordinators be trained to create a nurturing environment in which they regularly communicate to in-coming volunteers the organisation's appreciation for their donations of time and effort and gauge how they wish or need to be supported in carrying out their volunteer work. Lo Presti (2013) also argues that to ensure that volunteering experiences are highly rewarding and that volunteers become more committed, it is necessary for organisations to promote conditions characterised by higher levels of support (directed at both task and emotion), internal communication and feedback. Intention to Stay in the Organisation – key determinants Volunteers' Intention to Stay in the Organisation (IPO) is identified by Volunteer Management theorists and practitioners as one of the most desired outcomes of organisational practices, as it enables the organisation to retain its volunteers, manage financial resources more efficiently and have a stable group of human resources (an indispensable condition for ensuring consistent service delivery). Of the several constructs (concepts) referenced in the literature as directly or indirectly influencing the intention to stay in the organisation, I chose to focus my attention on three, in order to understand how they are related in the context of volunteering: the perceived organisational support, organisational connectedness and organisational commitment. Perceived Organisational Support was defined by Eisenberger et al. (1986) as employees' understanding of the extent to which the organisation appreciates their contribution and cares about their well-being. Levinston (1965, referred to by Eisenberger et al., 1986) noted that employees tend to view actions undertaken by agents of the organisation as actions of the organisation itself, and this personalisation of the organisation is underpinned by the following factors: (a) the organisation has a legal, moral and financial responsibility for the actions of its agents; (b) organisational precedents, traditions, policies and norms provide continuity and prescribe function behaviours; and (c) the organisation, through its agents, exercises power over individual employees. Employees develop overall beliefs regarding how much the organisation values their contributions and cares about their well-being, and this perceived organisational support depends on the same attributional processes that people generally use to infer other people's commitment to social relationships - ultimately, employees' commitment to the organisation is strongly influenced by their perception of the organisation's commitment to them. Organisational Connectedness is defined as a positive state of well-being that results from a strong individual sense of belonging to other employees of the organisation or service beneficiaries (Huyn et al., 2011). It may manifest itself in a human being's demand for interpersonal attachment, as well as in the need for attachment to the work itself or to the values of the organisation. Organisational Commitment is defined as a psychological state that characterises the relationship between the employee and the organisation and translates into the individual's willingness to dedicate significant time and effort to the organisation without a monetary objective (Meyer and Allen, 1997). This is one of the most studied organisational behaviour constructs in the context of volunteer management and of non-profit organisations themselves, as it is associated by management theorists and practitioners with outcomes that are particularly valued in an organisational context: loyalty, non-abandonment of the activity (Mowen et al., 1978), a higher quality service provision and the intention of long-term engagement with the organisation (Salas, 2009, cited by Séfora, 2016). Organisational commitment is considered as one of the main predictors of volunteers' intention to remain in the organisation (Salas, 2009; Vecina et al. 2013). Commitment is a multidimensional construct, usually distinguishing affective, instrumental and normative dimensions. In our research, we highlighted affective commitment, which refers specifically to the emotional or psychological attachment, identification with and participation in the organisation (Meyer & Smith, 2000). Affective commitment translates a strong relationship between a given individual and a specific organisation, and can be characterised by 3 factors: (1) being willing to exert considerable effort for the benefit of the organisation; (2) a strong belief in and acceptance of the organisation's goals and values; and (3) a strong desire to remain a member of the organisation (Porter & Smith, 1979). The Conceptual Model Figure 1

Conceptual Model The conceptual model, built on the literature review, which served as a basis for our research, proposes (1) that there is a direct causal relationship between perceived organisational support and affective organisational commitment, and (b) that organisational connectedness may play a mediating role in the relationship between perceived organisational support and affective organisational commitment.

Data collection and analysis Based on the model, I designed a questionnaire for people who do or have done regular volunteering with a minimum of one year of collaboration with the same organisation. The criterion of one year of collaboration with the same organisation was intended to guarantee a minimum time of exposure to the experience and practices of the organisation. In addition to questions characterising the sample, the questionnaire included three scales which had already been tested in the scientific literature: the scale used in the Survey on the Perceived Organisational Support (Eisenberger et al., 1986); the Four-Dimensional Connectedness Scale (Huyn et al, 2012); and the Three-Dimensional Organisational Commitment Scale (Dawley et al., 2005)], with the items of the first and second scales having been adapted to the volunteer context (this procedure was not necessary for the third scale, where this adaptation had already been made by the authors themselves). Aware of the importance of submitting the questionnaire to the largest possible number of volunteers, I contacted CASES - António Sérgio Cooperative for the Social Economy, with the request that he forward it to his database of volunteers. CASES’ response, made operational by Dr. Paula Correia and Dr. Teresa Lucas, exceeded my expectations, and I could count not only on the acceptance of my request, but also on a competent and committed collaboration in the fine-tuning of the questionnaire. I also asked 700 non-profit organisations to forward the questionnaire to their volunteers, and this request was favourably received by several organisations. 323 volunteers kindly decided to answer the questionnaire, and this set of people reported regular collaboration (present or past) with a total of 218 Portuguese non-profit organisations, as well as volunteering experience in a total of 50 countries, including Portugal. The data collected was analysed using descriptive statistics and structural equation analysis (using SmartPLS 3 software). Results As I mentioned, this research was designed to understand the relationship between perceived organisational support and affective organisational commitment, which is considered a predictor of the decision to stay in the organisation, and to assess the possible mediating role played by organisational connectedness in this relationship. The research produced positive results in terms of establishing the reliability and validity of the proposed measurement instruments. Quantitative data analysis confirmed the existence of a causal relationship between perceived organisational support and affective organisational commitment, as well as the hypothesis that organisational connectedness effectively acts as a full mediator in this relationship. In everyday language, this means that the more volunteers perceive that they are cared for by the organisation (whether in the scope of the functions and tasks they perform, or in emotional terms, when appropriate or necessary) the more they tend to dedicate themselves to the organisation, and to assume behaviours favourable to the pursuit of the organisational mission and objectives. As Eisenberger et al. (1986) put it, employees' commitment to the organisation is strongly influenced by their perception of the organisation's commitment to them. Furthermore, the impact of the perceived organisational support is found to be significantly leveraged, with an impact on affective organisational commitment, when volunteers feel a strong sense of belonging (connectedness) towards the organisation. Theoretical and Practical Implications of the Research In the context of volunteer work, in which the organisation does not have the classic tools of control - remuneration and work contract - it is essential that the volunteer feels that he/she has reasons to remain in the organisation. The perceived organisational support (Eisenberger et al. , 1986) and organisational connectedness (Huyn et al. , 2012) questionnaire items selected for the models after the structural equation analysis (for having higher factor loadings) give volunteer managers good clues for him/her to understand what can truly create a volunteer's attachment to the organisation and nurture their commitment to it: "The organisation values my contribution to its well-being (PAO); the organisation takes my goals and values seriously (PAO); when I have a problem, I count on the organisation for help (PAO); the organisation is available to help me when I need a special favour (PAO); the organisation cares about my overall satisfaction in volunteer work (PAO); the organisation is sensitive to my opinions (PAO); the organisation is proud of my achievements (PAO); the organisation tries to make my work as interesting as possible (PAO); I get along well with my peers and the staff of the organisation (VO); I am appreciated by the people I work with (VO); I have a feeling of belonging towards the people I work with in the organisation (VO); I enjoy doing volunteer work (VO); I am valued by the organisation (VO); My efforts as a volunteer are valued by the organisation (VO); the organisation appreciates my efforts (VO); I am treated fairly by the organisation (VO)". It is important that organisations choosing to rely on volunteers as a workforce, whether primary or complementary, are fully aware of:

Most volunteers choose to collaborate with the organisation of their own free will, driven by factors such as identification with the organisation's mission; previous knowledge of the organisation's activity; being inspired by the organisation's leaders. Underlying these motives are the needs that volunteers want to satisfy, often unconsciously. The volunteer activity is often the context in which a person is able to satisfy basic emotional needs such as affection, appreciation and security, or even not so basic needs such as the development of skills with professional applicability, the creation of a network of contacts, the search for the meaning of life, or even personal fulfilment. But for the satisfaction of these needs to happen consistently, by giving volunteers reasons to want to stay, the organisation must create the right environment and conditions, and this only happens when: (1) there is a respectful and welcoming attitude towards volunteers, who are carefully integrated and genuinely considered as full members of the organisation; (2) they keep an eye on each volunteer so that their needs and motivations are understood and their skills, preferences and constraints are taken into consideration in the choice of tasks, challenges, work teams, schedules and even the type of users they will serve; (3) there are people within the organisation who are primarily dedicated to volunteers, as internal clients, without whose satisfaction and involvement it may become unfeasible to provide services to the external client, the beneficiary of the organisation; (4) there is a conscious and consistent volunteer planning and management effort that takes into consideration the specificities and contingencies of the concrete organisation and succeeds in developing and implementing organisational attitudes and practices that ensure effective support (to work and emotions) of volunteer workers, that is perceived as such, that nurtures the emotional attachment (bonding) of employees to the organisation and that, ultimately promotes organisational commitment - it is not about implementing all volunteer management practices, but rather about understanding which ones produce better results, in the context of that particular organisation and, if possible, with less effort and allocation of resources (particularly in organisations with weaker resources); (5) there is an awareness that the way each practice is implemented influences the volunteers' perception more than the practice itself - and to this extent, we cannot fail to highlight the importance of communication, which, as one of the previously identified volunteer management practices, is possibly the one that, if properly implemented, can respond more directly to the basic emotional needs of volunteers, and ensure the adequacy and effectiveness of all the others that may be implemented (training, recognition). Sometimes a word of appreciation at the end of a difficult volunteer shift from a colleague or coordinator, or a pep talk when faced with a difficulty, is more meaningful for a volunteer than the recognition award he/she receives on stage in front of hundreds of people at the end of the year. Those moments become precious when, in a training course or team activity, a new friendship is made; or when you have the opportunity to meet some beneficiaries of volunteer work in person, with whom you had only spoken by telephone; or when you can help to make things happen through the expression of some personal talent (carpentry, cooking, painting, repairs, writing, drawing, dancing, or others). If we could summarise in a few words what a significant proportion of volunteers want is to feel that he/she are loved and valued, that he/she matters, that he/she is useful, that he/she is learning and developing, that he/she is able to make a difference in someone's life. Volunteer coordinators play a central role in this, and it is important that they are able to assume volunteers as their main internal clients - and not as another resource to be used to serve beneficiaries and achieve organisational goals. In line with Lo Presti (2013) and Boezeman & Ellemers (2007), mentioned above, we believe that, by continuously and consistently (from the first contact) caring for the relationship between the volunteer and the whole human universe of the organisation (other volunteers, management team, paid employees, users) it is possible to create truly rewarding and meaningful experiences that promote a sense of belonging and importance, capable of developing happy and truly committed volunteers for the organisation. BIBLIOGRAPHY

ALFES, K, SHANTZ, A. & BAILEY, C. (2015). Enhancing volunteer engagement to achieve desirable outcomes: What can non-profit employers do? VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 27, 595-617. BOEZEMAN, E. J., & ELLEMERS, N. (2007). Volunteering for charity: Pride, respect, and the commitment of volunteers. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92, 771-785. CLARY, E. G., SNYDER, M., & RIDGE, R. (1992). Volunteers' motivations: A functional strategy for the recruitment, placement, and retention of volunteers. Nonprofit Management and leadership, 2 (4), 333-350. DAWLEY, D, STEPHENS, R. & STEPHENS, D. (2004). Dimensionality of organizational commitment in volunteer workers: Chamber of commerce board members and role fulfillment. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 67 (2): 511-525. EISENBERGER, R., HUNTINGTON, R., HUTCHISON, S. & SOWA, D. (1986). Perceived Organizational Support. Journal of Applied Psychology, 71 (3), 500-507. The American Psychological Association. GIDRON, B. (1984). Predictors of retention and turnover among service volunteer workers. Journal of social service research, 8 (1), 1-16. HAGER, M. A., & BRUDNEY, J. L. (2004). Balancing act: the challenges and benefits of volunteers. Washington: The Urban Institute. HAGER, M. A., & BRUDNEY, J. L. (2011). Problems Recruiting Volunteers - Nature vs Nurture. Nonprofit Management & Leadership, 22, n.2. HUYNH, J. Y., METZER, J. C., & WINEFIELD, A. H. (2011). Engaged or connected? A perspective of the motivational pathway of the job demands-resources model in volunteers working for nonprofit organizations. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 23 (4), 870-898. LO PRESTI, A. (2013). The interactive effects of job resources and motivations to volunteer among a sample of Italian Volunteers. Voluntas - International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 24 (2), 969-985. MEYER, J.P.& ALLEN, N.J. (1997). Commitment in the workplace: Theory, Research and Application. SAGE Publications MEYER, J. P., & SMITH, C. A. (2000). HRM practices and organizational commitment: Test of a mediation model. Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences/Revue canadienne des sciences de l'administration, 17 (4), 319-331. MOWDAY, R. T., STEERS, R. M., & PORTER, L. W. (1979). The Measurement of Organizational Commitment. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 14, 224-247. Omoto, A. & Snyder, M. (1995), Sustained helping without obligation: motivation, longevity of service and perceived attitude change among aid volunteers. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 68 (4), 671-86. SALAS, Emílio (2009). Claves para la Gestión del Voluntariado en las Entidades no Lucrativas. Madrid: Fundación Luis Vives. SEFORA, N. S. M., & MIHAELA, T. T. (2016). Volunteers trust in organizational mission, leadership and activities efficiency. annals of the university of Oradea, Economic Science Series, 25 (1). VECINA, M. L., CHACÓN, F., MARZANA, D. & MARTA, E. (2013). Volunteers Engagement and Organizational Commitment in Nonprofit Organizations: what makes volunteers remain within organizations and feel happy? Journal of Community Psychology, 41, (3), 291-302. WALK, M., ZHANG, R., & LITTLEPAGE, L. (2019). "Don't you want to stay?" The impact of training and recognition as human resource practices on volunteer turnover. Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 29 (4), 509-527. |